mediaphone/wax

Wax Cylinders and the Early History of Sound Recording in the Mediterranean

The wax cylinder as a commercial item: The Flamenco Cylinders

This first part of Mediaphone looks at the earliest moments of sound recording in the Mediterranean basin, starting from a fragile and often overlooked object: the wax cylinder.

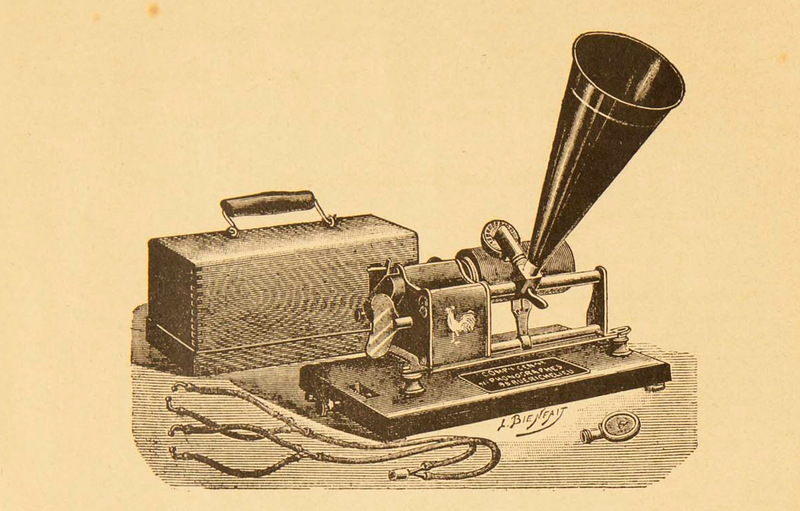

The sound that opens the program is a Peteneras from El Mochuelo, recorded in 1907. It was captured using a phonograph, a late nineteenth-century technology and the first system capable of both recording and reproducing sound. The process was entirely mechanical. Sound vibrations moved a diaphragm and were engraved as a continuous groove onto the surface of a rotating wax cylinder. When played back, that groove was traced again and the sound re-emerged.

Wax cylinders were the first widely used sound recording format, and also one of the most vulnerable. They were highly sensitive to heat and humidity, and they wore down quickly with repeated playback. Many cylinders deteriorated within a few years of being made. What survives today is often partial, noisy, or damaged. Even so, the phonograph introduced a decisive shift. Sound could now be fixed into an object, stored, transported, and circulated independently of live performance.

In Spain, early commercial recording focused heavily on flamenco. Singers were recorded extensively, and forms such as peteneras, seguiriyas, and malagueñas were among the repertoires captured on wax cylinders. These recordings document specific ways of singing shaped by Andalusian, and especially Romani-Gitano, communities and working-class environments. At the same time, they reflect a moment when southern Spain was increasingly folklorized and exoticized through Northern European cultural frameworks, producing a particular form of internal orientalism within Europe.

The wax cylinder as musical investigation tools: Bela Bartok in Turkey

Around the same period, recording technologies began to attract the attention of musicians and composers interested in traditional music, not as commercial material, but as something to be documented and studied. In these cases, the phonograph functioned as a research tool. It allowed melodies, rhythms, and performance practices to be captured directly, often in rural contexts where music circulated orally and was closely tied to everyday life.

Two central figures in this history are Romanian musicologist Constantin Brăiloiu and the Hungarian composer Béla Bartók. Bartók, in particular, carried out extensive field recording work across Hungary, Romania, and Turkey. In 1936, he traveled to Anatolia to record secular songs and instrumental traditions among village and Yörük communities in southern Turkey1.

These wax cylinders document local vocal and instrumental practices connected to work, seasonal cycles, and community celebrations. Bartók was interested in how these melodies related to one another across regions. Rather than treating traditions as isolated national forms, he listened for musical connections across Anatolia, the Balkans, and the wider Mediterranean.

By the time Bartók made these recordings, the phonograph was no longer dominant in commercial sound reproduction. Formats such as shellac discs had largely replaced it. Yet the phonograph remained useful for fieldwork due to its portability and its adaptability to outdoor recording conditions.

The wax cylinder as a tool of control: North African archives in Berlin and Paris

Tunisian cylinders

More broadly, sound recording in the early twentieth century became embedded in research and colonial forms of knowledge production.

In ethnography and related disciplines, researchers used the phonograph to record music directly where it was performed, with the aim of documenting musical structures, vocal techniques, and performance practices. One important example is the work carried out in Tunisia during the 1920s by the German scholar Robert Lachmann2.

His wax cylinder recordings document a wide range of musical practices associated with different communities. They include Jewish liturgical and paraliturgical songs from the island of Djerba, rooted in a long-standing Jewish presence in southern Tunisia3. They also include recordings labeled as Bedouin music, documenting rural and nomadic vocal traditions from south-eastern regions of the country4. These recordings capture music tied to religious life, oral transmission, and local social environments.

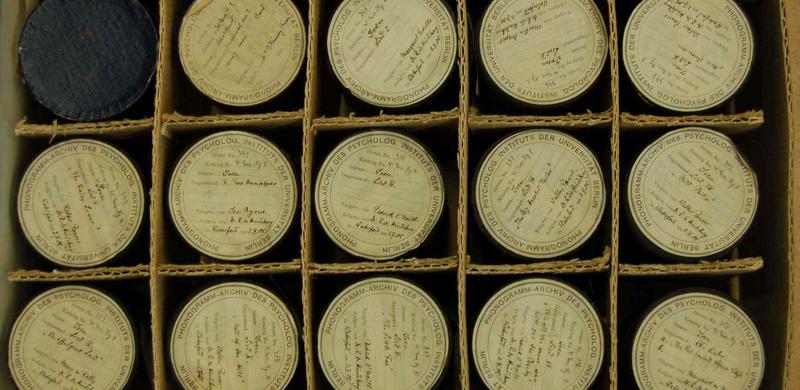

The material produced during this fieldwork was not archived locally. Instead, it was transferred to institutions in Europe.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, large phonographic collections were centralized in archives such as the Berliner Phonogramm-Archiv5 and the Vienna Phonogrammarchiv6. Founded around 1900, these institutions aimed to document and classify musical and linguistic traditions from outside Western Europe. In practice, this meant that recordings from the Mediterranean and other regions were gathered, transported, and preserved in central European collections. Operating within broader colonial and imperial frameworks, these archives played a decisive role in shaping how recorded music was categorized, contextualized, and understood. As a result, much of the earliest phonographic documentation of non-Western musical traditions is preserved far from the places where it was recorded.

Some recent initiatives attempt to address these issues by improving access and reconsidering archival practices, especially in relation to recordings from the Arab world7.

Algerian cylinders

Early phonographic recording in Algeria offers another revealing example.

The recordings made during 1935 and 1936 document musical practices of Chaouïa Amazigh communities living in the Aurès mountains, a rural region of eastern Algeria. The wax cylinders capture collective vocal performances and instrumental pieces associated with social gatherings, seasonal rituals, and communal life.

These recordings preserve oral traditions transmitted outside written notation. At the same time, they reflect the growing influence of colonial ethnography, which increasingly sought to record and classify Amazigh cultures, often framing these traditions as timeless or isolated while removing their cultural expressions from local contexts and depositing them in metropolitan archives.

Today, these recordings are preserved in the archives of Université Paris Nanterre, accessible online [^Nanterre].

The wax cylinder as an orientalization tool: Universal Exposition of 1900

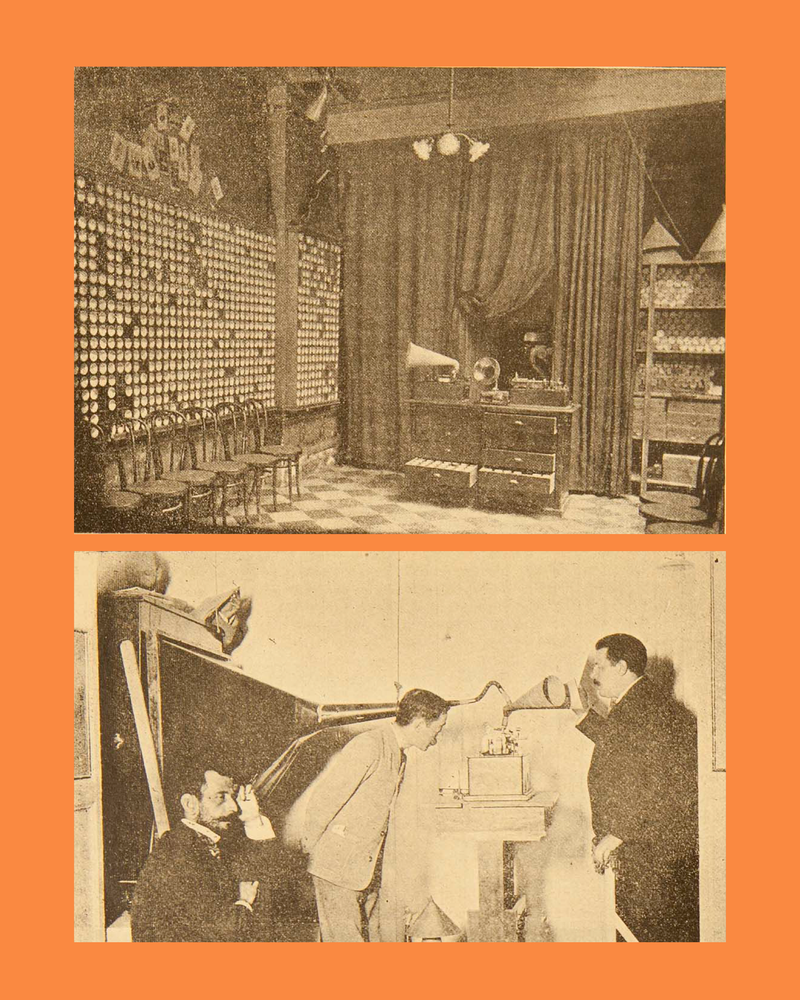

Within the same archival collections, we also encounter recordings produced specifically for the Universal Exposition of 1900 in Paris 8.

These recordings were created for exhibition rather than research. They reflect the logic of world fairs at the turn of the century, where music was presented as cultural display, detached from its original contexts and arranged to fit imperial narratives. Examples include Kabyle, Moroccan, and Syrian songs recorded for the exposition.

Access to the waxes: Adriatic and Palestinian cylinders

We will finally end the program by continuing our exploration of the Berliner Phonogramm-Archiv, this time from the Adriatic Sea region to Palestine9, reflecting how access to these early phonographic recordings remains limited, especially for researchers and for communities in the regions where the music was originally recorded. Many of these collections were created within colonial frameworks and remain difficult to access online today. This raises important questions about control, circulation, and responsibility when it comes to recorded cultural heritage. A critical approach to these archives is necessary. This means acknowledging the historical conditions under which the recordings were produced, while also rethinking how they might be shared, contextualized, and engaged with in more equitable ways.

The next part of Mediaphone will continue this exploration by turning to shellac recordings, the format that followed wax cylinders and played a central role in shaping the circulation of Mediterranean music throughout the twentieth century.

References

-

Famous travelers to Türkiye: Bela Bartok, Hungarian composer, collector of folk music, Daily Sabah ↩

-

From Wax Cylinder to Metal Disc: Transplanting Robert Lachmann’s “Oriental Music” Project from Berlin to Jerusalem on the Eve of World War II, the world of music ↩

-

Lachmann 1929 (174 Lachmann Tunesien), lachmann.tn ↩

-

Lachmann 1927 (165 Lachmann Bedouin), lachmann.tn ↩

-

The Collections of Music from the Arab World in the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv, the world of music ↩

-

The Complete Historical Collections 1899-1950, Austrian Academy of Sciences ↩

-

Access to Waxes – The Collections from the Arab World of the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv: Between Digitization, “Repatriation,” and Online Publication, the world of music ↩

-

Exposition Universelle 1900: sélection numérisée en 2005, LESC - CREM ↩

-

Helfritz Palestine, Deustche Digitale Bibliothek ↩